Postoperative infections continue to pose a major challenge in orthopedic surgery. When surgical site infections occur, they often result in prolonged hospital stays, increased health care costs and significant distress for patients. This leads to worse health outcomes, higher morbidity and even increased mortality. (1) Antibiotic prophylaxis remains an important tool to lower this risk of infection.

Postoperative infections continue to pose a major challenge in orthopedic surgery. When surgical site infections occur, they often result in prolonged hospital stays, increased health care costs and significant distress for patients. This leads to worse health outcomes, higher morbidity and even increased mortality. (1) Antibiotic prophylaxis remains an important tool to lower this risk of infection.

However, open fractures present unique considerations that complicate both the evidence for and the approach to antimicrobial therapy. The key is balance — providing effective antibiotic coverage to prevent these infections, while also maintaining antibiotic stewardship to minimize resistance and adverse effects. Clinical decisions must therefore be guided by available evidence and individual patient risk factors.

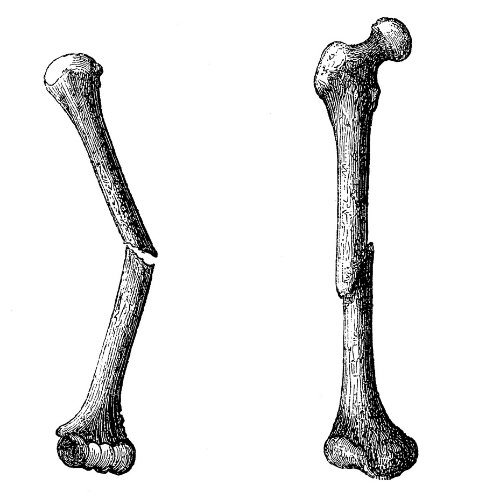

Open fractures are often high-energy injuries, and because bone and deep tissue are directly exposed to the environment, they carry a particularly high risk of postoperative infection, wound complications and nonunion. (2) Modern medicine has certainly improved outcomes — thanks to antibiotics, careful surgical debridement and internal fixation — but the core principles of treatment haven’t really changed since World War I: primary asepsis, thorough debridement, immobilization and protecting the wound from further contamination.

To help guide treatment, improve communication and even predict prognosis, the Gustilo-Anderson classification was devised to describe open fractures by severity. (3) This widely used classification breaks them into three categories:

- Type I: A clean wound less than 1 cm long

- Type II: A laceration more than 1 cm long, but without major soft tissue damage, flaps or avulsions

- Type III: The most severe injuries, including segmental fractures, wounds with extensive soft tissue loss, or traumatic amputations.

This framework is more than just a classification — it directly informs how clinicians approach antibiotic use, surgical management and long-term care strategies.

A recent example

One recent case highlighting these challenges involved a 54-year-old patient who sustained a Type III open ankle fracture on the left side after a mechanical fall. The injury required external fixation, but the road to recovery was far from straightforward. Healing was slow, and the severity of tissue damage placed the patient at high risk for amputation. As the infectious diseases team, we were faced with a difficult balancing act — on one hand, the initial wound was open, heavily soiled from injury, and clearly needed broad and reliable antibiotic coverage to prevent seeding of infection; on the other, we had to remain mindful of antimicrobial stewardship principles to avoid overtreatment and creating resistance. (4)

In our patient’s case, the standard protocol of preoperative prophylaxis with cefazolin was promptly initiated, followed by thorough wound debridement and placement of a temporary external fixator. Given the severity of the extremity trauma, antibiotic coverage was broadened to ceftriaxone for three days while meticulous local wound care was provided during the inpatient stay.

There was some understandable uneasiness from our surgical colleagues, who were concerned that the antibiotic regimen might not be broad enough and suggested the possibility of adding intravenous aminoglycosides or extending the duration of therapy. However, in the absence of clinical or microbiological evidence to indicate poor wound healing — and with cultures remaining reassuring — we felt it was appropriate to stay the course rather than escalate unnecessarily.

On discharge, the patient was transitioned from ceftriaxone to oral amoxicillin-clavulanate for a total of seven days, with close follow-up from both the surgical and ID teams. Over the following two months, the wound gradually improved with intermittent local debridement and careful wound management. Importantly, no additional systemic antibiotics were required beyond the initial course, highlighting how a measured, stewardship-conscious approach can still achieve positive outcomes in high-risk open fractures.

Complex decision-making

This case underscored just how complex decision-making can be in managing open fractures, where both under-treatment and over-treatment have significant consequences.

Clinicians agree that first-generation cephalosporins remain the standard of care for perioperative prophylaxis in open fractures. For more severe injuries, particularly Type III and sometimes Type II fractures, additional gram-negative coverage is recommended to reduce the risk of infection. The typical duration of prophylaxis is around seven days. (5)

One important point to highlight is that, although these consensus guidelines suggest potential use of aminoglycosides for additional gram-negative coverage, we think this may not be the most practical option. With the availability of advanced generation cephalosporins and carbapenems, we now have agents that provide more reliable coverage without the same challenges of dosing and toxicity that aminoglycosides carry.

The take-home message: The choice of antibiotic regimen should be tailored to the individual patient, taking into account their risk factors, prior colonization history and overall clinical context.

References

- Shambhu S et al. The Burden of Health Care Utilization, Cost, and Mortality Associated with Select Surgical Site Infections. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2024;50(12):857-866.

- Coombs J et al. Current Concept Review: Risk Factors for Infection Following Open Fractures. Orthop Res Rev. 2022;14:383-391.

- Kim P and Leopold S. Gustilo-Anderson Classification. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(11):3270–3274.

- Upadhyyaya G and Tewari S. Enhancing Surgical Outcomes: A Critical Review of Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Orthopedic Surgery. Cureus. 2023;15(10):e47828.

- Goldman A and Kevin T. AAOS Clinical Practice Guideline Summary: Prevention of Surgical Site Infection After Major Extremity Trauma; J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2023;31(1):e1-e8.