The spaces we inhabit: How we shape them, how they shape us

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email Anyone who has ever worked in a hospital is aware of the different microclimates that coexist within a hospital building. Some sections can be sweltering, while others are simultaneously arctic.

Anyone who has ever worked in a hospital is aware of the different microclimates that coexist within a hospital building. Some sections can be sweltering, while others are simultaneously arctic.

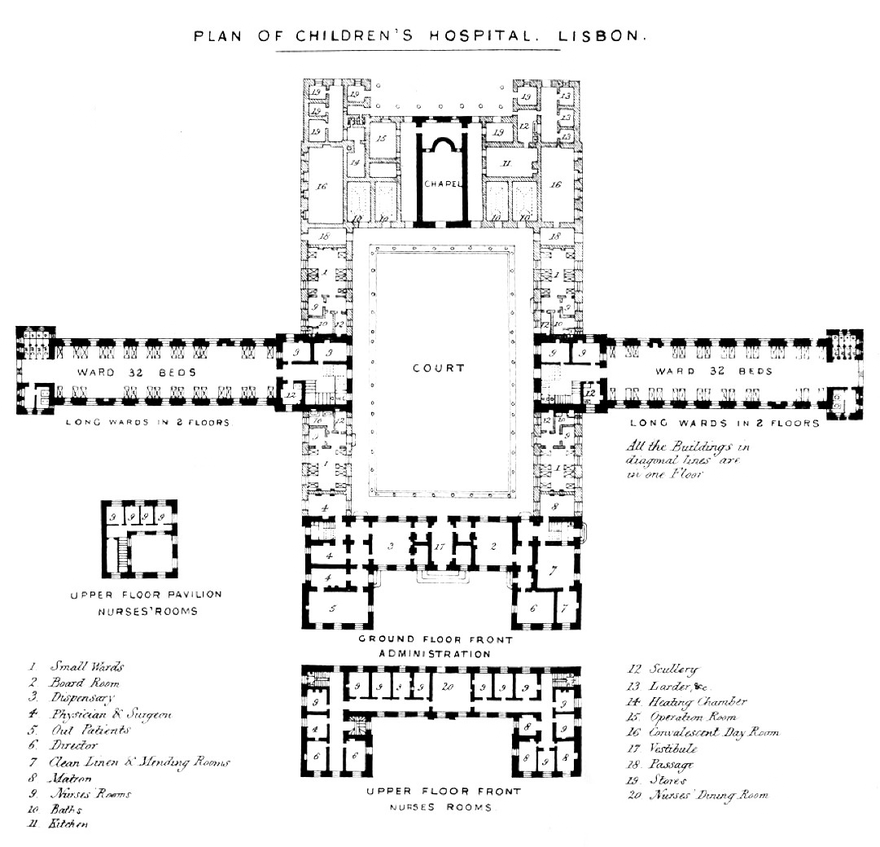

Our ID clinic was in the former zone one afternoon several weeks ago when the conversation turned to the phenomenon of sealed hospital windows, a consequence of safety concerns (preventing an opportunity for suicide attempts or accidental falls) and initiatives (somewhat ironically) to optimize temperature control and air flow within the hospital. A counterexample might be the pavilion plan hospital, sometimes called the Nightingale hospital, that prioritized access to light and fresh air and that dominated hospital design in the early 20th century.

These years of the COVID-19 pandemic have made us acutely aware of the spaces that we inhabit — how public spaces and the ways in which we relate in space shape our behavior and, conversely, how our ideas of safe spaces and distances influence the ways in which we organize and build the structures around us. Though we have once more become particularly conscious of this aspect of lived experience in the past few years, the concepts themselves are not new.

Exploring influences on hospital design and their effects

After the Second World War, the reciprocal relationship between designed spaces and the users of those spaces developed out of concerns that were nearly opposite to the forces that are shaping group dynamics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rather than social distancing, a watchword of the 1960s and 1970s was overcrowding. Increasing population density (and its accompanying problems) in cities fueled an interest in optimal urban and institutional design.

Social scientists in the 1960s began formally working out theories of personal space. Anthropologist Edward T. Hall, for example, coined the term “proxemics” to define the ways that humans interact within and with the spaces they inhabit. These theories were consciously incorporated into the architecture of hospital inpatient wards in the third quarter of the 20th century reflecting a renewed interest in “humanizing” hospital spaces.

Architectural historian Annmarie Adams has noted that writing on hospital design has tended to emphasize the transformative power of changing medical knowledge. The space of the hospital in these accounts serves more as a passive container for what takes place within rather than an active shaper of those activities. Adams pushed against this narrative. (1)

Jeanne Kisacky, writing a broader historical overview of hospitals throughout the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, agreed. She challenged her readers to consider to what extent does the hospital building itself actively exert an effect on those within it: “Should architecture be studied as a reflection of sociocultural transformations and aspirations? As a tool? Or as a force in molding and shaping it? As a therapy?” (2)

How we perceive spaces and their impact on us

Hall expanded on his ideas about proxemics in his influential book, The Hidden Dimension, published in 1966. He detailed the ways in which our senses, including proprioception and thermal sensation, contribute to our experience of space and concluded that “man’s relationship to his environment is a function of his sensory apparatus plus how this apparatus is conditioned to respond.” (3)

This experience of space operated outside the boundaries of conscious analysis. Hall also elaborated on the different ways that humans and other animals perceive the spaces between each other. He described theories of territoriality and spacing defined by the animal psychologist Heini Hediger, who distinguished between intimate distances between individuals — personal space and social space — and social spacing in the public sphere, which is directly affected by the design of the surrounding environment. (4) Intriguingly, Hall also examined cross-cultural differences in spatial perception.

Hall ultimately argued that lived space has the capacity to both affect one’s psychological and physiological state, and shape a person’s behavior. Lest we think that this sort of analysis is an academic exercise, Hall explicitly stated that “the relationship between man and the cultural dimension is one in which both man and his environment participate in molding each other… [such that] in creating this world he is actually determining what kind of an organism he will be [emphasis in the original].” (5)

This is quite an extraordinary statement. Hall essentially suggested that humans have the capacity to influence the direction of their own evolution via the built spaces that they create. If that is true, then we should perhaps all be a bit more aware of and thoughtful about the spaces we inhabit and build, sealed windows and all.

Image information: "Plan of Children's Hospital. Lisbon" from Notes on Hospitals, by Florence Nightingale, 1863; source: Wellcome Collection. To learn more about Nightingale's influence on hospital design, see this related article.

References

- Adams, A. Medicine by Design: The Architect and the Modern Hospital, 1893-1943. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 2008, p. xxv.

- Kisacky, Jeanne. Rise of the Modern Hospital: An Architectural History of Health and Healing, 1870-1940. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press; 2017, pp. 6-7.

- Hall, Edward T. The Hidden Dimension. Garden City, NY: Doubleday; 1966, p. 62.

- Hall, Hidden Dimension, pp. 8-15.

- Hall, Hidden Dimension, p 4.