Bridging the gap: HPV screening and gender inclusivity in Puerto Rico

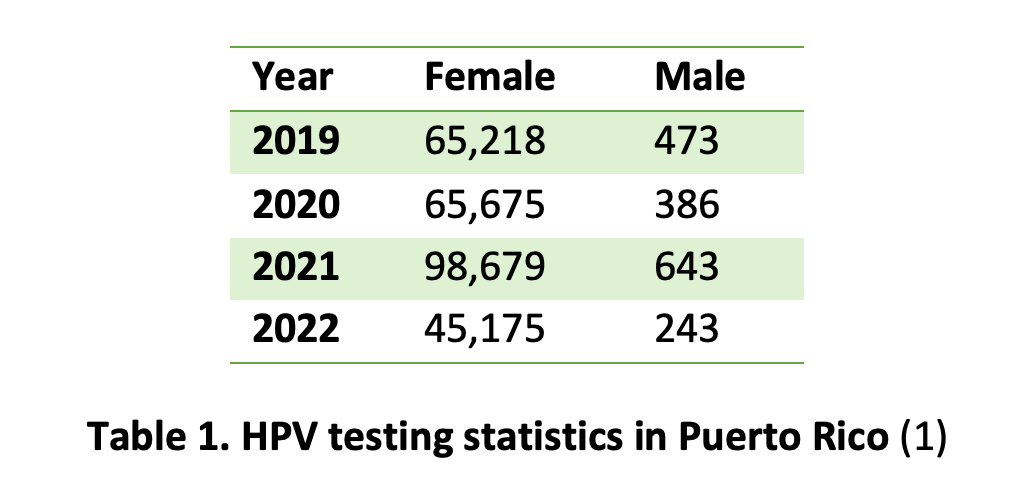

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email A recent analysis of human papilloma virus screening tests using medical claims data from Puerto Rico’s public health insurance program reveals a striking disparity: While thousands of women undergo HPV tests each year, only a fraction of men receive similar screenings. (1) For example, in 2021, nearly 100,000 women were tested compared to just 643 men. (Table 1)

A recent analysis of human papilloma virus screening tests using medical claims data from Puerto Rico’s public health insurance program reveals a striking disparity: While thousands of women undergo HPV tests each year, only a fraction of men receive similar screenings. (1) For example, in 2021, nearly 100,000 women were tested compared to just 643 men. (Table 1)

This disparity is not confined to Puerto Rico; it mirrors a global pattern in HPV testing practices between men and women, influenced by several key factors. Public health initiatives have primarily focused on cervical cancer, which affects only women. (2) As a result, screening tools like the Pap smear and HPV tests were specifically developed and widely adopted to identify precancerous or cancerous cells in the cervix. (2) In contrast, men do not have an equivalent screening method, and routine HPV screening for men remains underdeveloped. (3)

Currently, HPV screening in men is mostly restricted to anal Pap tests, which are primarily administered to men who have sex with men and those at high risk. (3) For the general male population, there are no approved routine HPV screening tests, resulting in a significant gap in the prevention and early detection of HPV-related cancers in men.

Cancer trends in men and a promising screening tool

Cancer trends in men and a promising screening tool

HPV is linked to several cancers in men, including penile, anal and oropharyngeal cancers. (3, 4) Recent epidemiological data show a concerning rise in cases of these cancers among men, with HPV being a significant contributing factor. This trend is particularly evident in regions with high Human Development Index scores, such as North America and Western Europe. (3) The lack of approved screening tests for men often results in these cancers going undetected until they reach advanced stages, underscoring the urgent need for more comprehensive HPV screening protocols that include men.

Circulating cell-free DNA is gaining recognition as a promising tool for liquid biopsy-based diagnostics. It has shown potential in aiding diagnosis, monitoring minimal residual disease, determining prognosis and identifying mutations that confer resistance across various cancers, including those associated with HPV, such as cervical cancer. (5,6,7) Ongoing research is investigating the use of cfDNA as a biomarker for HPV-related cancers in men, with a particular focus on early detection of penile, anal and oropharyngeal cancers through the analysis of HPV cfDNA from blood plasma. (5) These advancements hold significant promise for developing more effective screening methods for HPV-related malignancies across all genders.

Moving toward inclusive screening

As our understanding of HPV’s impact on both men and women evolves, so must our approach to screening and prevention. Expanding the availability and awareness of current HPV tests for men is crucial. At the same time, raising awareness about the risks of HPV in men and advocating for more inclusive screening guidelines are essential steps toward closing this public health gap.

The data from Puerto Rico serves as a stark reminder of the disparities in HPV testing and the work that remains to be done. By broadening screening efforts and developing more inclusive protocols, we can better protect everyone from the potentially devastating effects of HPV-related cancers.

Acknowledgments: The author would like to thank Dr. Ramón Scharbaai for his support and guidance at San Juan Bautista School of Medicine. His generosity in sharing data and providing feedback was key in shaping this article. The author is profoundly grateful for his guidance and encouragement throughout this process.

Photo: Colorized electron micrograph of HPV virus particles (pink) harvested and purified from cell culture supernatant. Captured at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Integrated Research Facility in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

References

- Scharbaai, R. (2024). HPV screening tests during COVID-19 pandemics. Unpublished manuscript.

- Okunade K. S. (2020). Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 40(5):602–608.

- Bruni, L., Albero, G., Rowley, J., Alemany, L., Arbyn, M., Giuliano, A. R., Markowitz, L. E., Broutet, N., & Taylor, M. (2023). Global and regional estimates of genital human papillomavirus prevalence among men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 11(9):e1345-e1362.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV and oropharyngeal cancer.

- Rosing, F., Meier, M., Schroeder, L., Laban, S., Hoffmann, T., Kaufmann, A., Siefer O., Wuerdemann, N., Klußmann, J. P., Rieckmann, T., Alt, Y., Faden, D. L., Waterboer, T., & Höfler, D. (2024). Quantification of human papillomavirus cell-free DNA from low-volume blood plasma samples by digital PCR. Microbiology Spectrum. 12(7):e00024-24.

- Clarke, M. A., Cheung, L. C., Lorey, T., Hare, B., Landy, R., Tokugawa, D., Gage, J. C., Darragh, T. M., Castle, P. E., & Wentzensen, N. (2019). 5-Year Prospective Evaluation of Cytology, Human Papillomavirus Testing, and Biomarkers for Detection of Anal Precancer in Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Positive Men Who Have Sex With Men. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 69(4):631-638.

- Parida, P., Baburaj, G., Rao, M., Lewis, S., & Damerla, R. R. (2024). Circulating cell-free DNA as a diagnostic and prognostic marker for cervical cancer. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer. 34(2):307–316.