Letermovir’s impact on CMV prophylaxis for seropositive HCT recipients and its role in CAR-T prophylaxis

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email Cytomegalovirus is a prevalent β-herpesvirus that typically remains dormant after primary infection. But it can reactivate during periods of immunosuppression, posing a significant threat to recipients of hematopoietic cell transplant. This reactivation is particularly common within the first 100 days post-transplant, often leading to a range of manifestations from asymptomatic viremia to severe tissue invasive disease. Historically, preemptive monitoring with anti-CMV therapy initiation upon detection of viral load above a threshold, often guided by institutional experience, was the norm due to concerns over toxicity associated with available treatments like valganciclovir, ganciclovir and foscarnet.

Cytomegalovirus is a prevalent β-herpesvirus that typically remains dormant after primary infection. But it can reactivate during periods of immunosuppression, posing a significant threat to recipients of hematopoietic cell transplant. This reactivation is particularly common within the first 100 days post-transplant, often leading to a range of manifestations from asymptomatic viremia to severe tissue invasive disease. Historically, preemptive monitoring with anti-CMV therapy initiation upon detection of viral load above a threshold, often guided by institutional experience, was the norm due to concerns over toxicity associated with available treatments like valganciclovir, ganciclovir and foscarnet.

These episodes of CMV reactivation that require antiviral treatment are referred to as clinically significant CMV infection, or CS-CMVi. However, a significant breakthrough came in 2017 with the publication of a phase 3 randomized controlled trial that demonstrated the efficacy of letermovir, a CMV viral terminase inhibitor, as prophylaxis for CMV reactivation in HCT recipients (1), offering a safer and more effective alternative. Following this development, letermovir received Food and Drug Administration approval for CMV primary prophylaxis, and common practice is to implement primary prophylaxis with letermovir at least until 100 days after HCT.

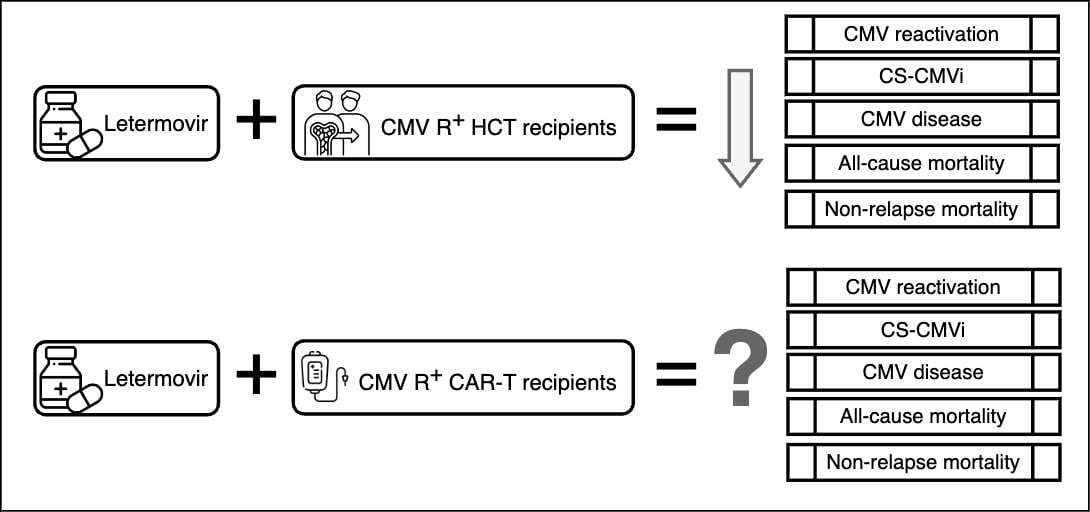

The impact of letermovir prophylaxis on CMV-seropositive HCT recipients has been further elucidated through multiple real-life cohort analyses (2), and its benefit goes beyond its impact on CS-CMVi. Most recently, our retrospective cohort study published in Clinical Microbiology and Infection further demonstrated the protective effects of letermovir related to lower all-cause and non-relapse mortality in CMV-seropositive HCT recipients. (3) Therefore, letermovir bridges the mortality gap previously observed in these patients compared to the CMV-seronegative HCT recipients. Duration of CMV prophylaxis in HCT is a matter of active research at the moment, and recent evidence supports that letermovir may be beneficial in preventing CS-CMVi up to day 200 with a less clear impact on mortality noted after day 100. (4)

In contrast, the role of letermovir prophylaxis in patients undergoing chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy remains less understood. While CAR-T therapy-induced immunosuppression predisposes patients to CMV reactivation (5), the optimal threshold for initiating anti-CMV treatment in these patients is yet to be determined. Expert opinions vary, with some advocating for preemptive therapy at lower viral load thresholds (detected DNA of < 1,000 IU/mL on RT-PCR). Others propose higher thresholds (at least 10,000 IU/mL) or the presence of end-organ disease as criteria for intervention. This uncertainty is compounded by the differing mortality risks associated with CMV reactivation in various patient populations, with those with acute myeloid leukemia treated with HCT at risk of higher mortality after CMV reactivation. This behavior differs from that seen in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. (6,7)

Navigating the complexities of CMV management in CAR-T patients requires a nuanced understanding of both the immunological dynamics of CAR-T therapy and the interplay between CMV reactivation and patient outcomes. As research continues to advance, it is essential to explore tailored approaches that consider the unique characteristics of individual patient populations, optimizing prophylactic strategies to minimize morbidity and mortality associated with CMV reactivation in this context.

In conclusion, while letermovir prophylaxis has revolutionized CMV prophylaxis in HCT recipients, its role in CAR-T patients remains uncertain. Addressing this knowledge gap requires further research to establish optimal thresholds for intervention and refine prophylactic strategies tailored to the specific needs of CAR-T recipients. As the field continues to evolve, collaborative efforts between clinicians, researchers and industry stakeholders will be essential in advancing our understanding and improving outcomes in this challenging clinical scenario.

References

- Marty FM, et al. Letermovir Prophylaxis for Cytomegalovirus in Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2017 Dec 21;377(25):2433-2444.

- Vyas A et al. Real-World Outcomes Associated With Letermovir Use for Cytomegalovirus Primary Prophylaxis in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022 Dec 22;10(1):ofac687.

- Febres-Aldana A, et al. Mortality in recipients of allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation in the era of cytomegalovirus primary prophylaxis: a single-centre retrospective experience. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2024 Mar 8:S1198-743X(24)00113-7.

- Russo D et al. Efficacy and safety of extended duration letermovir prophylaxis in recipients of haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation at risk of cytomegalovirus infection: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2024 Feb;11(2):e127-e135.

- Kampouri E et al. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Reactivation and CMV-Specific Cell-Mediated Immunity After Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2024 Apr 10;78(4):1022-1032.

- Mariotti J, et al. Impact of cytomegalovirus replication and cytomegalovirus serostatus on the outcome of patients with B cell lymphoma after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014 Jun;20(6):885-90.

- Schmidt-Hieber M, et al. CMV serostatus still has an important prognostic impact in de novo acute leukemia patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a report from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of EBMT. Blood. 2013 Nov 7;122(19):3359-64.